Grover: I got your fix, don't you want your fix?

Grover: I got your fix, don't you want your fix?Coffy: No, but you do.

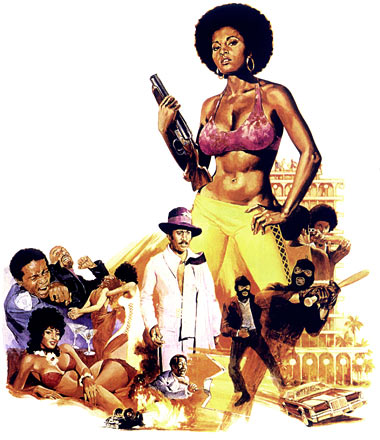

- Coffy (1973)

In her Introduction to The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir highlights the historical necessity for a patriarchy to maintain order; men who subscribe to this structure "still see in the emancipation of women a menace to their morality and their interests" (par. 21). Woman is seen as outsider rather than the normative, and thusly does not dictate power--nor does she tend, according to de Beauvoir, to reverse this paradigm. The prominent females in literature and film seem likelier to seek out a suitable partner than to combat their oppressors.

The social revolutions of the 1960s allowed for a greater exploration of sexuality and power structure; in the '70s, exploitation films intended for an urban black audience rose to prominence, some few of which starring women as central progatonists. There is little romance in these films, portraying life as a harsher, less idealized reality. Male characters are often criminal lords, ugly goons or drug dealers; women are prostitutes or are otherwise low in the hierarchy. Unlike the passive, unconsciously bonded woman of de Beauvoir's commentary, however, the Blaxploitation heroine is dissatisfied with the injustice of the status quo and seeks to correct wrongs herself.

Pam Grier portrays such a heroine in 1973's Coffy. A nurse driven to retaliation after her sister becomes a hospitalized addict, Coffy pretends to be a prostitute, even engaging in sexual encounters to infiltrate the world of the drug dealers and pimps responsible for her sister's downfall. She also has a romantic connection with two men: Howard, a wealthy politician, with whom her relationship is sexual, and Carter, a childhood friend and an honest cop, who maintains an unrequited love for Coffy.

Grier's presence in the film brings a multicultural ambiguity, as a "physically threatening but sexually appealing Amazon" (Reid 86). This brings a new level of complexity to the typical male-female Romance, and to the "Other". The Blaxploitation heroine is neither pure nor demure, using sex as well as violence to achieve her ends, which some may see as demeaning the Romantic value; such scantily clad heroines "appeal to a male ego that has been threatened by the rise of the women's liberation movement" (Reid 87), and suggests that this new "Other" is able to use her power of sexual enticement to bypass the norms of a Romantic relationship.

Some could claim that the role Coffy plays to achieve her goals--a prostitute, albeit a dominant queen over other prostitutes--serves to undermine the sense of female empowerment, that "most audiences consider these unsheathed Amazons as objects to be sexually and racially disempowered. The penetrating male heterosexist gaze does more to disarm these heroines than their actions do to empower the filmic image of black women" (Reid 88). However, it can also be argued that it highlights the struggle itself; Coffy does what she can, to accomplish what she feels she must. The levels of power in which she operates force her to penetrate the system in whatever manner she is able.

And penetrate she does. Simone de Beauvoir might have noted that "woman cannot even dream of exterminating the males" (par. 12), but Coffy does not settle for defeating her enemies and returning to the "right man;" by the end of the film her foes have been exterminated by her personally, and she emerges alone and without partner. Given, her actions are not a general intention to right the social wrongs of history. but vendettas motivated by personal loss. Coffy's story does not reflect an active attempt to reverse the history of hegemony, nor does it reflect a search for a perfect romantic match. Coffy faces off against women as well, particularly when she threatens a white prostitute for information, and flees when the pimp--a heavyset black woman--returns. This further redefines the concept of Romance, in that a sexually-suggestive conflict includes only women of differing ethnicities: "I come back and find you ballin' some n***** bitch! You white tramp!" (Harriet, in Coffy). Coffy also engages in a vicious combat with several prostitutes to gain a prominent drug lord's lecherous attention. It suggests a non-discriminating battle to the top rather than a battle of the sexes.

Why the departure from romantic norms? There is an "obvious" choice for male companion in the form of Carter, an upstanding citizen who cares deeply for Coffy. Howard is an uncertain choice, rich and charismatic and at first appearing to fight for civil rights. Carter is removed violently from the story, while Howard proves corrupt. Coffy, as independent heroine, must accomplish her aims without male aid; the "Other" is now an active, central force rather than an accompanying subordinate. The black heroine in these films may not be meant to provide something with which to identify, but rather to add to an already complex Other, and in the case of Coffy--who turns out to be more woman than her opponents can handle--also resists the tradition of the Romantic by creating a new, appealing Other.

WORKS CITED

Coffy. Dir. Jack Hill. Perf. Pam Grier, Booker Bradshaw, Robert DoQui, and William Elliott. MGM, 1973.

de Beauvoir, Simone. Introduction. The Second Sex. 1949. Marxists.org. 2005. 14 October 2008

Reid, Mark. "Black Action Film." Redefining Black Film. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993: 69–91.

No comments:

Post a Comment