Grover: I got your fix, don't you want your fix?

Grover: I got your fix, don't you want your fix?Coffy: No, but you do.

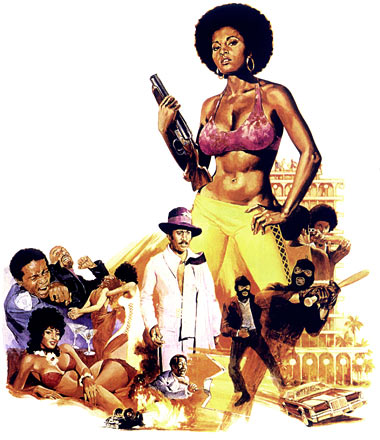

- Coffy (1973)

Note: This is a first draft of this paper, actually longer and more complete. I consider this a better paper than the one which was compressed down to a smaller, three-page format. - Dave Elsensohn

In her Introduction to The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir highlights the historical necessity for a patriarchy to maintain order, namely by keeping the female sex in an inferior position; men who subscribe to this structure "still see in the emancipation of women a menace to their morality and their interests" (par. 21). Woman is seen as outsider rather than the normative, and thusly does not dictate power--nor does she tend, according to de Beauvoir, to reverse this paradigm: ""Why is it that women do not dispute male sovereignty?" (par. 9). The prominent females in literature and film seem likelier to seek out a suitable partner than to combat their oppressors.

The social revolutions of the 1960s allowed for a greater visual exploration of sexuality and power structure in later decades; in particular, exploitation films intended for an urban black audience rose to prominence in the '70s, some few of which starring women as the central progatonists. There is little romance in these films, as they choose to portray life as a harsher, less idealized reality, a world of "racial dualism, explicit sexuality, and vengeful violence" (Reid 86). Male characters are often criminal lords, ugly goons or drug dealers; many of the women are prostitutes or are otherwise low in the hierarchy. Crime and revenge are a major plot theme. Unlike the passive, unconsciously bonded woman of de Beauvoir's commentary, however, the Blaxploitation heroine is dissatisfied with the injustice of the status quo and seeks to correct wrongs herself. There is little opportunity to savor a romantic relationship; almost all other characters in such a story are vile. Those are aren't are "punished" for their purity, indicating the film's world and its corruption.

A heroine such as Pam Grier portrays in 1973's Coffy brings a level of complexity to the socially typical male-female relationship, and introduces a new sense of "Other"--that of woman, that of black, that of one who does seek to dispute the "male sovereignty." Coffy is a nurse who is driven to retaliation after her sister becomes a hospitalized addict. Pretending to be a prostitute and even engaging in sexual encounters to get past obstacles, Coffy infiltrates the world of the drug dealers and pimps responsible for her sister's downfall in order to exact revenge. Aside from her intentional sexual exploits, she has a potential romantic connection with two men: one is Howard, a wealthy politician, with whom her relationship is sexual, and the other is Carter, a childhood friend and an honest cop, who maintains an unrequited love for Coffy.

Grier's presence in the film brings a multicultural ambiguity, as a "physically threatening but sexually appealing Amazon" (Reid 86). This, mainly, is what introduces the complication into Romance and into the Other: the Blaxploitation heroine is neither pure nor demure, and needs neither a male as protector nor societal approval. She uses sex as well as violence to achieve her ends, which some may see as demeaning the Romantic value; such scantily clad, hyper-sexual heroines "appeal to a male ego that has been threatened by the rise of the women's liberation movement" (Reid 87), and therefore suggest that the "Other" is able to use her power of sexual enticement to bypass the norms of a Romantic relationship. The body is yet another tool.

Some could claim that the role Coffy plays to achieve her goals--a prostitute, albeit a dominant queen over other prostitutes--serves to undermine the sense of female empowerment, that "most audiences consider these unsheathed Amazons as objects to be sexually and racially disempowered. The penetrating male heterosexist gaze does more to disarm these heroines than their actions do to empower the filmic image of black women" (Reid 88). It is historically apparent that the African-American female has been portrayed often in a purely physical sense, possibly for the sake of exoticism (admittedly, Coffy chose a "Jamaican" prostitute persona to play), possibly to continue a racist patriarchal image of the "naked savage." However, it can also be argued that her nudity and casual sexual encounters serve to highlight the struggle itself; Coffy does what she can, with what weapons she has at her disposal, to accomplish what she feels she must. The levels of power in which she operates force her to penetrate the system in whatever manner she is able.

And penetrate she does. Simone de Beauvoir might have noted that "woman cannot even dream of exterminating the males. The bond that unites her to her oppressors is not comparable to any other" (par. 12), but Coffy does not settle for defeating her enemies and returning to the "right man" for her; by the end of the film her foes have been exterminated by her personally--by shotgun, knife, car, et al--and she emerges alone and without partner. She even wields a sort of phallic dominance, in forcing a dealer to inject himself with a lethal needleful of heroine, and in leveling a shotgun at her disingenuous politican lover, who turns out to be in league with the drug dealers.

Given, her actions are not a general intention to right the social wrongs of history. but vendettas motivated by personal loss. Coffy's sister was brought low by a drug dealer. Carter is beaten into a coma when he refuses to take money to keep silent. The levels of power structure remain low and gritty. Coffy's story does not reflect an active attempt to reverse the history of patriarchal hegemony, nor does it reflect a search for a perfect romantic match despite her sexual appeal. The conflict also does not solely remain in the realm of Woman vs. Man; Coffy faces off against women as well, particularly in one scene where she threatens a white prostitute for information. She is forced to flee when the prostitute's pimp--a heavyset black woman--returns; this further redefines the concept of Romance, in that a sexually-suggestive conflict includes only women of differing ethnicities: "I go away for half an hour for you to turn a trick... and I come back and find you ballin' some n***** bitch! You white tramp!" (Harriet, in Coffy). Coffy also engages in a vicious combat with several prostitutes in an attempt to gain the lecherous attention of a prominent drug lord. It suggests a non-discriminating battle to the top rather than a battle of the sexes.

Why the departure from romantic norms? There is an "obvious" choice for male companion in the form of Carter, who is an upstanding citizen and cares deeply for Coffy. There is an uncertain choice in Howard, in that he is rich and charismatic at first, appearing to fight for civil rights. Carter is removed violently from the story, while Howard proves corrupt. It seems that Coffy, in her role as an independent heroine, must accomplish her aims without male aid. The "Other" is now an active, central force rather than an accompanying subordinate; to be otherwise would dilute the conflict and cast doubt on whether the womanly Other could be a solitary agent of change without male support. With Coffy's emergence alone from her trials, the Romantic aspect has been deconstructed; she is free to dictate her own future.

The black heroine in these films may not be meant to provide something with which to identify, but rather to add a level of complexity to an already complex Other. She also serves to unravel the concept of Other by obtaining a level of power equal to the male suppression she endures, although she does not waver from de Beauvoir's claim that Woman is not unified: Coffy is the sole protagonist, the action hero(ine). She is superior to other females, in the same way that a male action hero is superior to other males, and in the case of Coffy--who turns out to be more woman than her opponents can handle--also resists the tradition of the Romantic by creating a new, appealing Other.

WORKS CITED

Coffy. Dir. Jack Hill. Perf. Pam Grier, Booker Bradshaw, Robert DoQui, and William Elliott. MGM, 1973.

de Beauvoir, Simone. Introduction. The Second Sex. 1949. Marxists.org. 2005. 14 October 2008

Reid, Mark. "Black Action Film." Redefining Black Film. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993: 69–91.

No comments:

Post a Comment